Günümüzde online bahis, teknolojinin sunduğu imkanlarla her zamankinden ulaşılabilir hal aldı. Mobil cihazlarla giriş yaparak, evde ya da dışarıda, istediğiniz her yerden bahis alabilirsiniz. Ancak bu erişilebilirlik yeni bir sorun yaratıyor. Her geçen gün daha fazla bahis sitesi ortaya çıkıyor. Bu durum, doğru ve güvenilir olanı seçmeyi zorlaştırıyor.

Casino siteleri arasında seçim yaparken dikkat edilmesi gereken en önemli faktör, güvenilirlik ve kullanıcıya sunulan gerçek avantajlardır.

- All

200% Yeni Oyuncular İçin Hoş Geldin Bonusu – 25.000 €’ya Kadar + 50 Ücretsiz Döndürme

200% Yeni Oyuncular İçin Hoş Geldin Bonusu – 25.000 €’ya Kadar + 50 Ücretsiz Döndürme

- 4000+ kripto casino oyunu

- Yüksek ödüller ve hızlı işlemler

- Üst düzey güvenlik ve topluluk desteği

25.000$'a kadar 200% + 50 ücretsiz bahis + 10 ücretsiz bahis

25.000$'a kadar 200% + 50 ücretsiz bahis + 10 ücretsiz bahis

- Çevrimiçi spor bahisleri mevcut

- Büyük başlangıç bonusu

- Büyük ve etkili bir topluluğa sahip bir kumarhane

1 BTC'ye kadar 200% bonus + 50 bedava dönüş + ücretsiz spor bahisleri

1 BTC'ye kadar 200% bonus + 50 bedava dönüş + ücretsiz spor bahisleri

- Yenilikçi QuickBet modu oyuncuların tek bir tıklamayla bahis oynamasına olanak tanır

- Telegram veya web üzerinden en iyi sağlayıcıların oyunlarını oynayın

- Sık ödüllerle oyunlaştırılmış sadakat programı

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

7777 ₺'ye Kadar %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

7777 ₺'ye Kadar %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

Hoş Geldin! %100 15.000₺ İlk Üyelik Bonusu Casino'da!

Hoş Geldin! %100 15.000₺ İlk Üyelik Bonusu Casino'da!

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

10.000 ₺' %100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu

%100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu Casino İlk Üyelik Bonusu

%100 Casino Hoşgeldin Bonusu Casino İlk Üyelik Bonusu

15% Casino Yatirim Bonusu + 10% Free spin

15% Casino Yatirim Bonusu + 10% Free spin

Bir casino sitesine üye olmadan önce, bazı noktaları gözden geçirmek önemlidir. Öncelikle sunulan bonusların şartlarını inceleyin. Sonra oyun çeşitliliğine bakın. Ödeme yöntemlerini de kontrol edin. Ayrıca müşteri hizmetlerinin kalitesini değerlendirmek de faydalıdır.

Tercih edilen casino sitesinin lisanslı olup olmadığına ve gerçek kullanıcı yorumlarına göz atmak, sorunsuz bir deneyim yaşamanız açısından oldukça önemlidir.

Yalnızca yüksek bonuslara veya cazip oranlara odaklanmak, her zaman en iyi casino sitesini bulduğunuz anlamına gelmez. Asıl önemli olan, seçtiğiniz casino sitesinin vaat ettiği deneyimi gerçekten sunup sunmadığıdır.

Casino siteleri hakkında kapsamlı bir araştırma yaparak, sizlere en iyi oyun deneyimini sunan platformları bir araya getirdik.

Casino Siteleri İçinde Önce Çıkan Slot Siteleri

Casino siteleri günümüzde oyun severler arasında büyük ilgi görüyor ve online şans oyunları dünyasında kendine sağlam bir yer ediniyor. Slot siteleri, kolay oynanabilir olmaları ve çeşitli oyun seçenekleri sunmalarıyla popüler platformlar arasında yer alıyor.

Güvenilir casino sitelerinde slot oyunları oynayarak eğlenceli vakit geçirebilirsiniz. Ayrıca, çeşitli bonus ve promosyonlardan da yararlanırsınız. Özellikle deneme bonusu veren siteler ve en iyi slot siteleri, yeni kullanıcılara hem risksiz deneme imkânı sunar hem de yüksek kazanç fırsatları sağlar. Piyasada birçok seçenek var. Bu yüzden, casino ve slot siteleri arasında doğru seçimi yapmak önemlidir. Bu, güvenli ve keyifli bir deneyim için gereklidir. Aşağıda, sizin için güvenilir ve avantajlı özellikler sunan bir listeledik.

- Akcabet – Hızlı ödeme ve kolay para çekme avantajı

- Alibahis – Yatırımsız deneme bonusu veren ücretsiz seçenekleri çok olan site

- Betbaba – En iyi slot oyunları ve yüksek kazanç fırsatı

- Betivo – Kripto destekli güvenilir bahis sitesi

- BTCbahis – Yenilikçi altyapı, 2026’iin yeni bahis sitesi

- Casinomega – Mobil uyumlu, geniş oyun portföyü

- Efes Casino – Anında çekim ve yenilikçi canlı casino deneyimi

- Kazancasino – Üst düzey veri koruması 7/24 müşteri desteği

- Ozanbet –Güncel oranlar, en çok kazandıran slot oyunları

- Sultanbet – Lisanslı altyapı,global spor ve casino seçenekleri

- Wonodd – Şartsız deneme bonusu,mobil ve kripto uyumlu platform

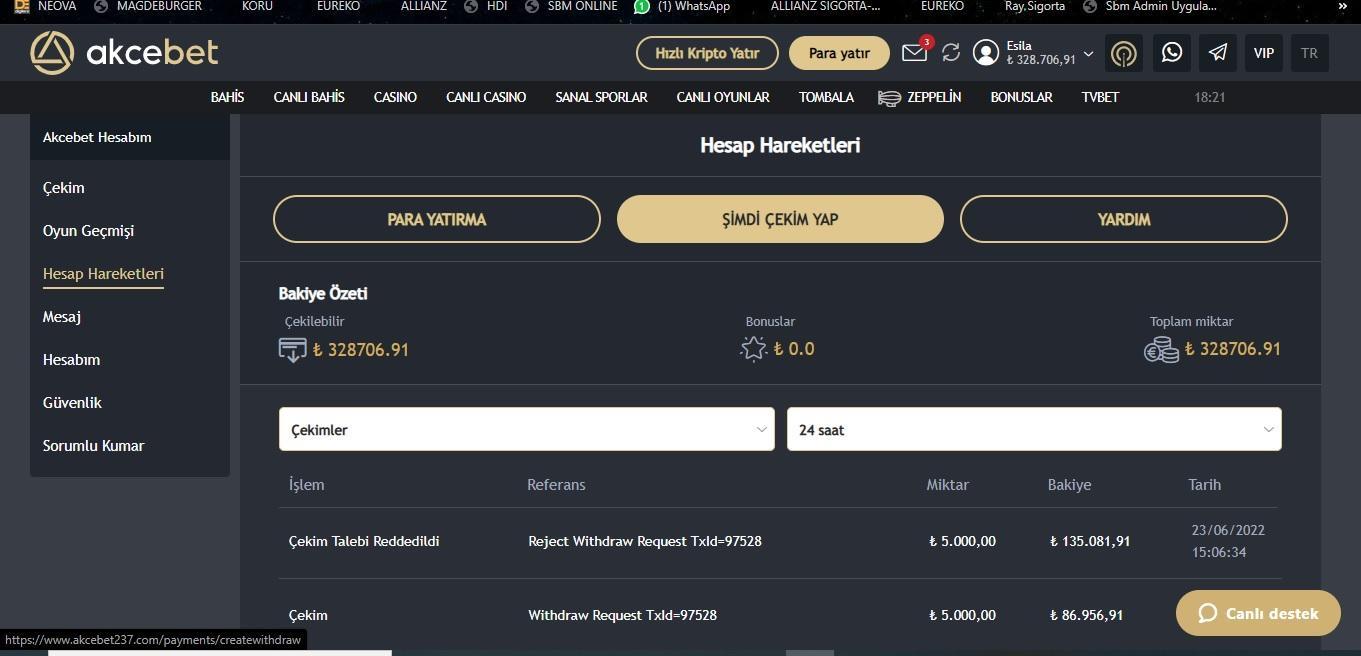

1. Akcabet – Yatırım Şartsız Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler 2026

Yoğun bir iş gününden sonra kendinize zaman ayırmak isterseniz, Akcebet harika bir seçenek. Yorgunluğunuzu unutmanıza yardımcı olabilir. Hem eğlenceli vakit geçirmek hem de kazanç şansınızı artırmak için Akcebet’in sunduğu ayrıcalıklı dünyaya kolayca erişebilirsiniz.

2014’ten bu yana hizmet veren Akcebet.com, online bahis ve casino siteleri arasında hem güvenilirliğiyle hem de geniş oyun yelpazesiyle öne çıkıyor. Bu platform, uluslararası Curacao lisansına sahiptir.

“Londra merkezli uzman ekibiyle Akcebet, Türkiye’nin en yüksek hacimli bahis ve slot siteleri arasında yer alır. Güçlü finansal altyapısı ve sunduğu cazip avantajlarla sektörde lider konumdadır. Hem yeni başlayan oyunculara hem de deneyimlilere hitap eden geniş yelpazesiyle dikkat çeker.”

Akcebet, canlı bahis ve VIP hizmetleri ile dikkat çeker. Mobil uyumlu altyapısı sayesinde, istediğiniz her yerden oyun oynamanın tadını çıkarabilirsiniz. Platformda, renkli slot makineleri, rulet, blackjack ve poker gibi klasik casino oyunları var. Ayrıca, canlı krupiyelerle gerçek zamanlı oyunlar da mevcut.

Akcebet, oyuncularına binlerce oyun seçeneği sunmanın yanı sıra, futbol, basketbol ve tenis gibi popüler spor dallarının yanı sıra farklı branşlarda da bahis yapma imkânı tanır. Ayrıca platform, çeşitli bonus fırsatlarıyla da dikkat çeker.

Yeni üyelere özel 200 TL deneme bonusu, yatırımlarınızda ise %15 çevrimsiz yatırım bonusu ile anında avantaj sağlar. Casino tutkunları için %25 casino yatırım bonusu ve %20 spor bonusu fırsatları var. Ayrıca, kayıplarınız için %20 kayıp spor bonusu ile destek sağlanır. Bu sayede, Akcebet’te hem kazancınızı artırabilir hem de daha uzun süre keyifle oyun oynayabilirsiniz.

Güvenlik konusunda taviz vermeyen Akcebet, kullanıcı bilgilerinin gizliliğini ve korunmasını her zaman öncelikli tutar. Tüm kişisel verileriniz güncel şifreleme teknolojileriyle korunur. Yalnızca yetkili personel bu bilgilere erişebilir. Şifre veya kart bilgileriniz gibi hassas veriler ise her zaman güvende kalır.

Ödeme yöntemleri konusunda Akcebet.com, kullanıcılarına hızlı ve güvenli birçok alternatif sunuyor.Hesabınıza para yatırmak veya çekmek için şu hızlı casino transfer seçeneklerini kullanabilirsiniz: Anında Banka Havalesi, CepBank, Hızlı Havale ve QR Kod. Ayrıca Jeton, kredi ya da banka kartı, Bitcoin ve Papara gibi popüler yöntemlerle de kolayca işlem gerçekleştirebilirsiniz.

Ayrıca Jeton, kredi ya da banka kartı, Bitcoin ve Papara gibi popüler yöntemlerle de kolayca işlem gerçekleştirebilirsiniz. Tüm bu seçenekler, hem güvenli hem de hızlı finansal işlemler sunar.

Tüm finansal işlemler üst düzey güvenlik önlemleriyle gerçekleştirilir ve kişisel bilgileriniz özenle korunur. Herhangi bir ödeme sorununda, canlı destek hattına ya da [email protected] adresine yazabilirsiniz.

Akcebet, kurulduğundan beri müşteri memnuniyetine odaklanıyor. Yüksek bahis oranları, avantajlı bonuslar ve geniş oyun seçenekleri sunuyor.Eğer güvenilir casino ve slot siteleri arıyorsanız, Akcebet.com iyi bir seçenek. Kolay ödeme yöntemleri ve güçlü müşteri desteği sunuyor.

Artılar

- Hesap oluşturma ve doğrulama işlemlerinin hızlı olması

- Bitcoin, Papara ve diğer dijital varlıklarla kolay işlem imkanı

- Zengin canlı bahis ve slot oyun çeşitliliği

- 7/24 canlı müşteri desteği

Eksiler

- Bazı ödeme yöntemleri tüm kullanıcılar için aktif olmayabilir

- Yalnızca belirli ülkelerden erişim sağlanabiliyor

- Sitede dil seçenekleri sınırlı

- Bonus çevrim şartları yeni başlayanlar için karmaşık gelebilir

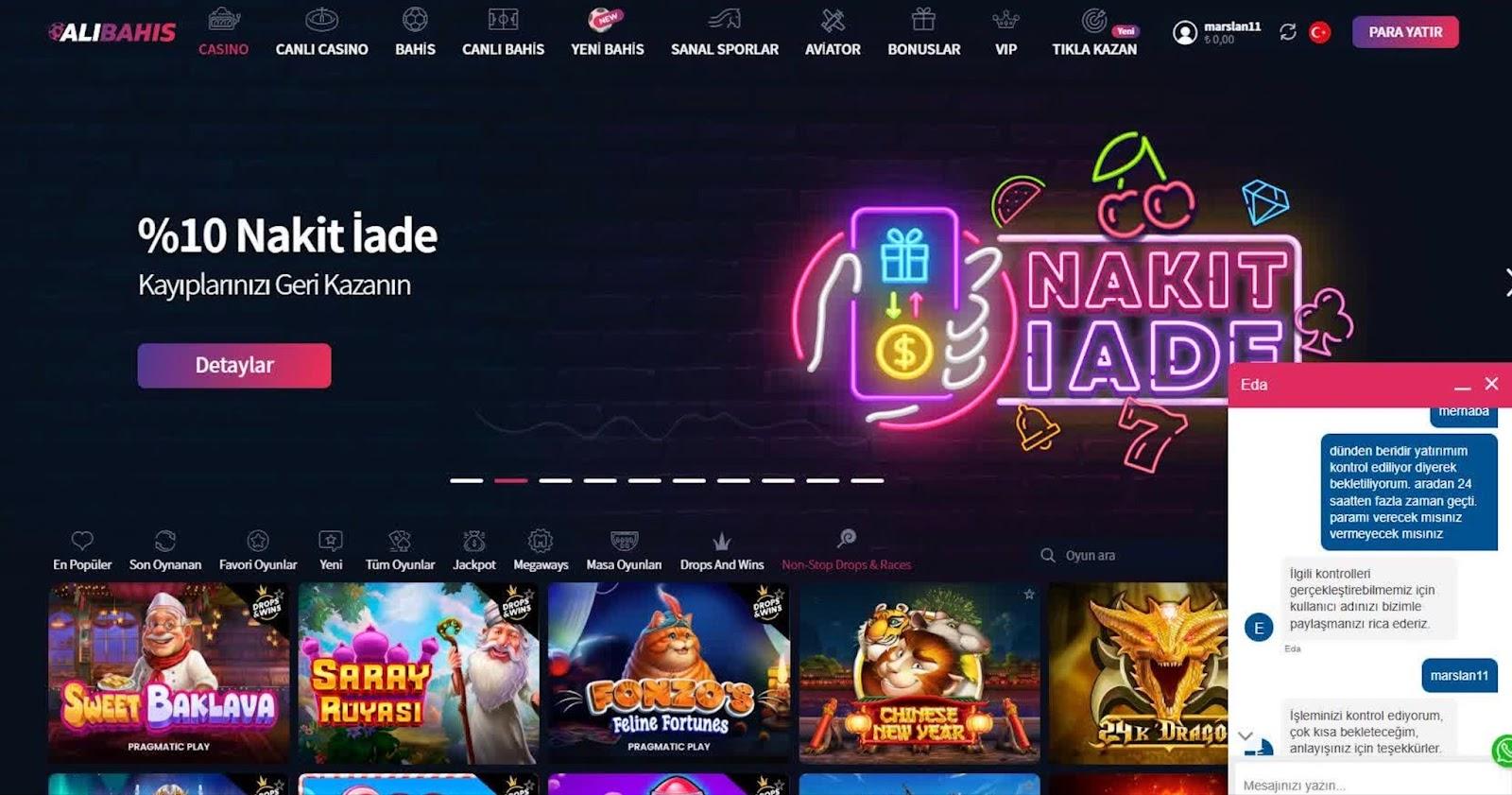

2. Alibahis – Kolay Para Çekme ve Hızlı Ödeme Avantajı Sunan Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler

Keyifli vakit geçirmek ve aynı zamanda kazanç elde etme şansı yakalamak istiyorsanız, Alibahis sizi benzersiz bir oyun dünyasına davet ediyor. Alibahis, üyelerine hız ve güven sunar. Finansal işlemlerinde şeffaflık sağlar ve %100 müşteri memnuniyeti hedefler.

Yılın 365 günü, 24 saat kesintisiz hizmet verir. Alibahis’e uygulama indirmeden, sadece tarayıcı ile girebilirsiniz.Güncel bonus fırsatları ile geniş oyun seçeneklerinin tadını çıkarın. Ayrıca, yeni kullanıcılar için deneme bonusu sunan siteler arasında yer alıyor.

Alibahis, Curacao lisansı ile yasal olarak faaliyet göstermektedir. Üyelerinin tüm kişisel ve finansal bilgilerini üst düzey güvenlik protokolleriyle korur. Kimlik ve belge doğrulama işlemlerinde tamamen kullanıcı güvenliğini ön planda tutar. Gizlilik politikası gereği, bilgileriniz hiçbir şekilde üçüncü şahıslarla paylaşılmaz.

Spor bahisleri ve casino için çeşitli yatırım bonuslarıyla kullanıcılar ek avantaj elde edebilir. Hoşgeldin bonusları, platforma yeni katılan üyeleri teşvik ederken; kayıp bonusları ve nakit iadeler ise yaşanan kayıplara karşı destek sağlar. Ayrıca, free spin ve bedava bahis fırsatları da ekstra kazanç şansı sunar.

Alibahis, casino ve slot siteleri arasında zengin oyun portföyüyle öne çıkar. 20’den fazla sağlayıcıyla binlerce oyun seçeneği sunuyor. Klasik masa oyunları, rulet, blackjack ve poker de var. Ayrıca, renkli slot makineleri ve yenilikçi canlı casino deneyimleri de mevcut. Güvenilir casino siteleri arasında gösterilmesiyle kullanıcalar tarafından tercih edilmektedir.

Canlı Casino bölümünde gerçek krupiyelerle oyun oynayabilirsiniz. Rulet, Blackjack, Bakara ve Poker gibi oyunlar sizi gerçek bir kumarhane ortamına götürür. Alibahis, sürekli güncellenen oyun seçenekleriyle her seviyeden oyuncuya hitap ediyor.

Alibahis, VISA, MasterCard ve Troy gibi kartlarla para yatırma ve çekme imkanı sunar. Ayrıca Jeton, Jeton Card, Papara, Jet Papara, Hızlı Havale, Anında Havale ve Cepbank ile işlemleriniz hızlıca gerçekleşir. Jet Kripto, My Kripto ve Anında QR gibi modern yollarla güvenli ve şeffaf finansal işlemler yapabilirsiniz. Ayrıca, Euro, Dolar ve TL cinsinden hesap açma seçeneğiniz de var. Bu yönüyle hızlı casino deneyimi yaşamak isteyenler içinde uygundur.

Alibahis, müşteri memnuniyetini en ön planda tutar. 7/24 canlı destek ve hızlı e-mail iletişimiyle, yaşadığınız her türlü sorun ve soruya anında çözüm sunar.

Artılar

- Zengin casino ve slot oyun çeşitliliği

- Onlarca ödeme yöntemi ile kolay finansal işlemler

- 7/24 canlı destek ve müşteri memnuniyeti

- Yüksek oranlar ve çeşitli bonuslar

Eksiler

- Sadece belirli ülkelerde hizmet vermesi

- Bonus çevrim şartlarının yeni başlayanlar için karmaşık olabilmesi

- Bazı ödeme yöntemlerinin kısıtlı bölgelerde kullanılması

3. Betbaba – Zengin Oyun Seçenekleriyle En İyi Slot Siteleri

Yoğun ve yorucu bir günün ardından güvenilir bir ortamda hem eğlenmek hem de kazanç fırsatı yakalamak istiyorsanız, Betbaba tam size göre! 2016’da Avrupa’da kurulan Betbaba, spor bahisleri, canlı bahis, casino ve canlı casino oyunları sunuyor.

Betbaba, casino siteleri ve slot siteleri arasında en geniş oyun portföylerinden birine sahip. Betbaba, Avrupa’nın en iyi altyapı sağlayıcılarıyla çalışıyor. Burada, çeşitli oyunlar bulacaksınız. Slot makineleri, rulet, blackjack, poker ve baccarat gibi klasik masa oyunları mevcut. Ayrıca, canlı casino masaları da var.

Betbaba, deneme bonusu veren siteler listesinde de yer alır; kullanıcılarına avantajlı bonuslar ve çeşitli promosyonlar sunar. %100 Limitsiz Casino Bonusu, %100 Limitsiz Spor Bonusu, Ecopayz’e özel %30 Casino ve Spor Bonusu, %30 Casino ve %30 Spor Bonusu,%15 Çevrimsiz Casino ve Spor Bonusu, %15 Anlık Kayıp Bonusu (Casino/Spor), %50, 5000 TL Gece Bonusu, %15 Geri Ödeme Bonusu 4000 TL Arkadaşını Getir Bonusu Büyük ödüllü slot turnuvaları ve daha fazlası!

Betbaba, bahis siteleri ve casino severlere hızlı ve çeşitli ödeme seçenekleri sunar.Cepbank, Anında Havale, QR Kod, Jeton Cüzdan, Jeton Kart, Bitcoin, Ecopayz ve Papara gibi popüler yöntemlerle hızlı ve güvenli para yatırma veya çekme yapabilirsiniz.

Minimum yatırım ve çekim limitleri yönteme göre değişiklik gösterir ve tüm bilgiler ödeme sayfasında yer alır. Hesap güvenliğini artırmak için çoklu doğrulama ve ek belge talebi gibi önlemler alınır.

Betbaba, Continental Solutions Ltd B.V. tarafından sağlanır. Lisanslı casino siteleri arasında yer alan platform, Curacao lisansına sahiptir. Bu nedenle, tamamen yasal ve uluslararası denetime tabidir. Müşteri gizliliği ve veri koruması Betbaba için çok önemlidir.

Betbaba, 7/24 canlı destek ekibi ve profesyonel müşteri temsilcileriyle, ihtiyacınız olan her an yanınızda. Her türlü soru ve finansal işlem için canlı destekten anında yardım alabilirsiniz. Ayrıca, [email protected] adresine e-posta atarak da iletişim kurabilirsiniz.

Artılar

- Avrupa standartlarında lisanslı ve güvenilir altyapı

- Çok çeşitli ve yüksek oranlı bonuslar

- Kapsamlı ödeme yöntemleri (kripto, ecopayz, papara vs.)

- 7/24 kesintisiz canlı destek

Eksiler

- Bazı ödeme yöntemlerinde bekleme süreleri değişken olabilir

- Bonus çevrim kuralları yeni başlayanlar için detaylı olabilir

- Sadece belirli ülkelerde hizmet verilmesi

4. Betivo – Yenilikçi Altyapısıyla 2026’in Yeni Bahis Siteleri

2016 yılında Avrupa’da kurulan ve kısa sürede Türkiye’de de büyük bir oyuncu kitlesine ulaşan bahis siteleri arasında öne çıkan online bahis ve casino platformudur. Betivo, yenilikçi yaklaşımı ve genç, dinamik kadrosuyla dikkat çeker.

En gelişmiş güvenlik altyapısına sahiptir ve şeffaf bir hizmet sunar. Lİsanslı casino siteleri statüsünde yer alan Betibo, Curacao lisanslıdır ve Continental Solutions Ltd B.V. tarafından denetlenmektedir.

Betivo, spor bahisleri, canlı bahis, sanal oyunlar ve daha fazlasını sunar. Casino, canlı casino, tombala ve online poker gibi geniş bir oyun yelpazesi vardır. Dünya çapında ünlü sağlayıcıların (NetEnt, Pragmatic Play, Playson, vb.) bulunduğu slot siteleri ile arasında dikkat çeker.

Betivo, binlerce slot oyunu sunar. Ayrıca, gerçek krupiyelerle canlı casino masaları ve yüksek oranlı spor bahisleri de vardır. Bu sayede, her kullanıcı profiline uygun eğlenceyi tek bir çatı altında toplar. Özellike popüler bahis siteleri arasında kısa sürede kendine sağlam bir yer edinmiştir.

Betivo, kullanıcılarına %100 limitsiz spor ve %100 limitsiz casino bonusu, %30 spor ve casino yatırım bonusu, %15 çevrimsiz casino ve spor bonusu, %15 anlık kayıp ve %15 haftalık kayıp bonusu, ayrıca arkadaşını getirene 2.000 TL’ye kadar bonus ve geceye özel %50 bonus gibi çeşitli kampanyalar sunmaktadır.

Bonuslar sadece eğlenceyi artırmakla kalmaz, aynı zamanda kullanıcının kazancını da katlama fırsatı sunar.Betivo’da finansal işlemleriniz için kredi kartı, Papara ve Jetpapara, Jeton ve Jeton Card, Bitcoin, Astropay, Cepbank, Hızlı Havale ve Anında QR gibi hızlı ve güvenli ödeme yöntemlerini kolayca kullanabilirsiniz. Ödemeler gelişmiş SSL şifreleme ve çok aşamalı güvenlik prosedürleriyle korunur.

Betivo, kullanıcı bilgilerinin korunmasını ve veri gizliliğini birincil öncelik olarak benimser. 256-bit SSL şifreleme, güvenlik duvarı, gelişmiş KYC süreçleri ve düzenli güvenlik kontrolleriyle üyelerinin bilgilerini korur. Tüm işlemler yasal çerçevede ve Curacao lisansı altında gerçekleşir.

Betivo, 7/24 hizmet veren profesyonel canlı destek ve e-posta ile müşteri hizmetleriyle, kullanıcılarına VIP seviyesinde hızlı ve çözüm odaklı destek sunar. Sorular, para yatırma-çekme işlemleri ve her türlü teknik konuda “bir tık” uzağınızda çözüm bulabilirsiniz.

Artılar

- Yenilikçi, genç ve dinamik platform

- Geniş spor, canlı casino, slot ve masa oyunu seçeneği

- VIP kalitesinde, 7/24 müşteri desteği

- Gelişmiş veri güvenliği ve hızlı ödeme yöntemleri

Eksiler

- Yenilikçi, genç ve dinamik platform

- Geniş spor, canlı casino, slot ve masa oyunu seçeneği

- VIP kalitesinde, 7/24 müşteri desteği

5. BTCbahis – Güvenilir ve Popüler Bahis Siteleri

BtcBahis, Türkiye’nin en güvenilir bahis siteleri ve en hızlı şans oyunları platformlarından biri olarak, sektördeki uzun tecrübesiyle öne çıkıyor.

BtcBahis, Curacao lisansı ile güvenilir bir casino sitesidir. Güçlü teknik altyapısı sayesinde, yılın her günü, 24 saat kesintisiz ve %100 güvenli hizmet sunar. BtcBahis’te finansal işlemler, müşteri memnuniyeti ve kullanıcı gizliliği her zaman en ön planda tutulur.

BtcBahis, tek bir maç için 2000’den fazla bahis seçeneği ve yüksek oranlar sunarak, spor bahislerinde rakiplerinden ayrışır. Tüm büyük ligler ve branşlar için hızlı ve kapsamlı bahis siteleri arasında fark yaratır.

20’den fazla sağlayıcı ve binlerce farklı casino oyunu, BtcBahis’in en büyük avantajlarından biri. Canlı Casino’da ise Rulet, Blackjack, Bakara ve Poker gibi klasiklerin yanı sıra, yenilikçi masa ve şov oyunları da sizi bekliyor. Slot siteleri tutkunları içinde binlerce oyun alternatif sunmaktadır. Gerçek krupiyelerle masa başı keyfini 7/24 yaşayın.

BtcBahis, üyelerine sürekli güncellenen ve kazanç odaklı bonus kampanyaları sunar. Deneme bonusu veren siteler arasında yer alan Btcsbahis, 200₺ deneme bonusu (bonus kodu ile), her yatırımda %15 üst limitsiz çevrimsiz bonus, 10.000₺ %100 casino hoşgeldin bonusu, 2.000₺ %100 spor hoşgeldin bonusu, %20 üst limitsiz spor yatırım bonusu, %25 limitsiz casino yatırım bonusu ve spor, casino ile canlı casino’da geçerli %20 anlık kayıp bonusu gibi fırsatlar bulunur. Tüm bonusların net çevrim kuralları ve çekim limitleri şeffafça belirtilmiştir.

BtcBahis’te kredi kartı, Papara ve Jetpapara, Jeton ve Jeton Card, Bitcoin, Astropay, Cepbank, Ecopayz, Hızlı Havale ve Anında QR gibi birçok popüler ödeme yöntemi bulunur ve tüm işlemler yüksek güvenlikli altyapı ile hızlı onay süreciyle tamamlanır.

Kişisel bilgiler, finansal hareketler ve tüm kullanıcı verileri en yüksek standartlarda korunur. 7/24 Canlı Destek, e-posta ve detaylı rehberlerle BtcBahis, her zaman üyelerinin yanında. Pozitif, hızlı ve çözüm odaklı destek ekibiyle tüm sorunlarınız kısa sürede çözüme kavuşur.

Artılar

- Yüksek oranlar, geniş bahis seçeneği

- Zengin bonuslar ve kolay çevrim şartları

- Geniş ödeme yöntemleri, hızlı para yatırma-çekme

- 20’den fazla sağlayıcı, binlerce casino ve slot oyunu

Eksiler

- Çekimlerde ve bonuslarda kimlik doğrulama zorunlu olabilir

- Bonus çekim üst limitleri bazı kullanıcılar için düşük bulunabilir

- Sadece bir hesap kuralı, aile üyelerine kısıtlama getirebilir

- Bonus talepleri ve işlemler bazen manuel onay gerektirebilir

6. Casinomega – Geniş Oyun Portföyüne Sahip En İyi Slot Siteleri

2014’ten bu yana Türkiye’nin en yüksek işlem hacmine sahip online bahis siteleri biri arasında hizmet veriyor. Curacao lisansı, güçlü finansal yapısı ve İngiltere merkezli yönetimi ile öne çıkan Casinomega, kullanıcı gizliliği ve güvenliğine en üst düzeyde önem verir. Müşteri memnuniyeti ve hızlı finansal işlemler konusunda sektörde kendini kanıtlamış olan site, modern ve mobil uyumlu arayüzüyle de fark yaratıyor.

Tüm işlemler yüksek güvenlik önlemleri ve şifreleme teknolojileriyle korunur. EGT, Netent ve Pragmatic Play gibi önde gelen sağlayıcılarla çalışıyoruz. Binlerce slot ve masa oyunu sunuyoruz. Ayrıca kapsamlı spor ve canlı bahis seçeneklerimiz var. 7/24 para yatırma ve çekme işlemleri yapabilirsiniz. Bitcoin ve Papara gibi birçok ödeme yöntemi mevcut.

Hoş geldin, yatırım, kayıp ve anlık bonuslarla, oyunculara yüksek avantajlar sağlar. Kullanıcı bilgileri asla üçüncü şahıslarla paylaşılmaz.

Casinomega, kullanıcılarına cazip bonus ve promosyonlar sunar. Deneme bonusu veren siteler arasında yer alan Casinomega, 200₺ deneme bonusu, 10.000₺ %100 casino hoşgeldin bonusu ve 1.500₺ %100 spor hoşgeldin bonusu ile yeni üyelere avantaj sağlar. Ayrıca %15 çevrimsiz yatırım bonusu, %25 üst limitsiz casino bonusu ve %20 spor ile casino kayıp bonusu gibi ek fırsatlar da sunulmaktadır. Bunlara ek olarak, yıl boyunca devam eden büyük ödüllü NON-STOP Drop turnuvaları da kullanıcıları bekliyor.

Casinomega, kullanıcı bilgilerinin korunmasını ana öncelik olarak görür. Tüm işlemler şifrelenmiş ve yüksek güvenlik protokolleri ile yürütülür. Hesaplar için kimlik doğrulama ve 18+ yaş sınırı titizlikle uygulanır. Gizlilik politikası açık ve şeffaftır; bilgiler üçüncü şahıslarla paylaşılmaz.

Casinomega, üyelerine güvenli bir oyun deneyimi sunar. Bunun için çeşitli oturum ve yatırım limitleri belirler. Ayrıca, hesap dondurma ve profesyonel yardım bağlantıları da sağlar. Canlı destek ve e-posta hattımız 7/24 hizmetinizde. Bize [email protected] üzerinden ulaşabilirsiniz. Casinomega, Türkiye’de bahis siteleri ve casino oyunları için güvenli, hızlı ve yüksek bonuslu bir deneyim sunar.

Artılar

- Yıllardır sektörde, yüksek işlem hacmi ve güçlü finansal altyapı

- Geniş oyun ve bahis marketi

- 7/24 kesintisiz, hızlı ödeme ve müşteri desteği

- Yüksek hoşgeldin ve kayıp bonusları, bol promosyon

- En iyi oyun sağlayıcılarla iş ortaklığı

Eksiler

- Bonus çevrimleri ve şartları yeni başlayanlar için karmaşık gelebilir

- Kayıt sırasında detaylı kimlik ve yaş doğrulama gerekebilir

- Bazı ödeme yöntemlerinde ek onay süreçleri olabilir

- Sıkı IP/cihaz sınırlamaları (her IP/cihaz için tek hesap)

7. Efes Casino – Hızlı Ödeme ve Geniş Bonuslarla Yeni Açılan Bahis Siteleri

Uzun yıllardır Türkiye bahis sektörünün öncülerinden biri olan Efes Casino, kullanıcılarına güvenli, sorumlu ve adil bir şans oyunları deneyimi sunar. 2008’den beri faaliyet gösteren bu platform, Curaçao merkezli Continental Solutions Limited B.V. tarafından işletilmektedir. Ayrıca, geçerli bir işletme sertifikası ile hizmet vermektedir.

Yeni nesil casino ve bahis oyunlarını, modern bir arayüzle sunar. Ayrıca, zengin ödeme seçenekleriyle kullanıcılarına ulaşır. Efes Casino, yeni açılan bahis siteleri arasında kısa sürede adını duyurmayı başarmıştır.

NetEnt, Pragmatic Play, Playson gibi dünyanın önde gelen oyun sağlayıcılarıyla çalışıyor. Casino, canlı casino, poker, bingo, kazı kazan ve turnuva bölümleriyle hem klasik hem yenilikçi oyun çeşitliliği sunuyor.Ayrıca, slot siteleri kategorisinde de farklı oyun seçenekleriyle öne çıkar.

Canlı casino bölümünde gerçek krupiyelerle Rulet, Blackjack, Bakara ve Poker gibi masa oyunlarında gerçek kumarhane heyecanı yaşanabiliyor. Oyunlar, düzenli güncelleniyor ve farklı kategorilerde yeni seçenekler ekleniyor. Efes Casino, bahis siteleri arasında, hem klasik hem yenilikçi oyunlarla her seviyeden oyuncuya hitap eder.

Efes Casino, yeni ve mevcut üyelerine cazip bonuslar ve promosyonlar sağlıyor:%100 limitsiz casino & spor bonusları, ilk üyeliklerde yüksek avantaj!. %30’a varan limitsiz casino ve spor yatırım fırsatları. Anlık ya da haftalık kayıplara %15’e varan nakit iade. Çevrim şartı olmadan direkt kullanılabilir casino/slot bonusları. Referans ile üye kazandıranlara özel bonuslar. Düzenli slot turnuvalarıyla milyonlarca liralık ödül havuzları.

Tüm bonuslar ve promosyonlar, şeffaf çevrim kuralları ve kullanım koşullarıyla sunulmaktadır. Kötüye kullanım veya çoklu hesap tespitinde, bonus iptali veya üyelik engeli uygulanabilir.

Minimum ve maksimum limitler, yönteme göre değişmekle birlikte, çekimler genellikle aynı gün içinde sonuçlanıyor. Tüm işlemler 256-bit SSL şifreleme ile korunuyor.

Efes Casino, Curaçao lisanslı casino siteleri arasında yer alır ve yasal işletme sertifikasına sahip bir sitedir. Efes Casino, veri güvenliği için çoklu güvenlik duvarı, gelişmiş şifreleme ve kapsamlı KYC/AML (Müşterini Tanı ve Kara Para Aklamayı Önleme) prosedürleri uygular. Bu nedenle, kullanıcılar için güvenlik her zaman birinci önceliktir. Efes Casino, güvenilir casino siteleri arasında yer alır.

Efes Casino, Türkiye’ye özel ve uluslararası birçok hızlı ödeme yöntemiyle öne çıkar. Anında havale ve CepBank, Papara, Jeton, Jeton Card, Jet Papara, Jet Kripto Cüzdan gibi popüler seçeneklerin yanı sıra; Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, Ripple, USDT ve Dogecoin gibi kripto paralar ile ödeme imkanı sunar. Ayrıca Visa, MasterCard, AstroPay Wallet ve QR Kod ile kolayca yatırım ve çekim yapılabilir; tüm bu işlemler için 7/24 canlı destek sağlanmaktadır.

Kişisel bilgileriniz, sadece şirket ve yasal otoritelerle paylaşılır; üçüncü kişilerle kesinlikle paylaşılmaz. 18 yaş altı üyelikler yasaktır ve tespitte hesaplar kapatılır.Efes Casino, kullanıcı memnuniyetine önem verir ve 7/24 Canlı Destek ile kesintisiz hizmet sunar. Sorularınızı ya da şikayetlerinizi [email protected] adresine e-posta ile de iletebilirsiniz.

Efes Casino, hem deneyimli hem de yeni oyuncular için güvenli ve eğlenceli bir online şans oyunu platformudur. Geniş oyun seçenekleri, cazip bonuslar ve güçlü güvenlik altyapısıyla öne çıkar. Ayrıca profesyonel bir destek ekibi ile hizmet sunar. Efes Casino, sorumlu ve yasal bahis için güvenilir bir adres olmaya devam ediyor.

Artılar

- Uzun yıllara dayanan tecrübe ve köklü marka

- Geniş casino, canlı casino ve bahis seçeneği

- Çok çeşitli ödeme yöntemleri ve hızlı çekim

- Yüksek bonus ve ödüllü turnuvalar

Eksiler

- Yalnızca belirli ülkelerden üyelik kabulü (ABD, İngiltere ve bazı ülkeler hariç)

- Bonus ve promosyon çevrim şartları yeni başlayanlar için karışık gelebilir

- Çoklu hesap açanlar/bonus suistimali yapanlar için sert yaptırımlar

- Kimi ödeme yöntemleri bazı bölgelerde sınırlı olabilir

8. Kazancasino – Güvenlik ve Kullanıcı Memnuniyetiyle En Güvenilir Bahis Siteleri

Kazancasino, Curaçao yasalarına göre kurulmuş ve sektördeki güvenilir casino siteleri arasında yer almaktadır. Novi B.V. bu casinoyu 155510 sicil numarasıyla işletmektedir. Ayrıca, Curaçao Oyun Kontrol Kurulu tarafından lisanslı casino siteleri statüsünde değerlendirilir. Amacımız, müşterilerimize adil ve güvenilir ortam sağlamak.

Bahis yalnızca eğlence amaçlı oynanmalıdır. Kayıpların peşinden koşmak, borç almak veya maddi sorunlar için bahis oynamak önerilmez. 18 yaşından küçükler sitemizde bahis oynayamaz. Kimlik ve yaş doğrulama prosedürlerimiz titizlikle uygulanır. Aileler için; çocukların erişimini kısıtlayacak filtre yazılımlarının kullanılması önerilir (NetNanny, CyberSitter vb.).

Ana para ve bonus çevrim şartları yerine getirilmeden çekim yapılamaz. Bonuslar genellikle casino oyunlarında 30x, spor bahislerinde 8x çevrim şartına tabidir. Kazançlarınızı çekebilmeniz için ana parayı en az bir kez oynamanız gerekir. Bonuslar başka promosyonlarla birleştirilemez ve belirli kurallara tabidir.

Kazancasino’da kullanıcılar için sunulan başlıca bonus ve promosyonlar ; %100 Casino-Slot Bonusu, %100 Üst Limitsiz Spor Bonusu, %30 Kripto Bonusu, %15 Çevrimsiz Bonus, Her Gün %25 Bonus, %50 Pazar Günü Bonusu gibi zengin seçeneklerdir.Ayrıca, deneme bonusu veren siteler arasında yer alması ile de yeni kullanıcıların ilgisini çekmektedir.

Para Yatırma ve Çekme Yöntemlerine baktığımız zaman karşımıza ; Moneytolia,VIP Havale,Jet Banka Transferi Auto Papara / Papara,Payfix, Oto Bank Transfer QR Kod, Jetoncash, Jeton Cüzdan,Kredi Kartı,Cepbank Kripto yöntemleri çıkmaktadır. Bu yöntemlerle bahis siteleri ve slot siteleri ile öne çıkmaktadır.

Kullanıcı bilgileriniz ve finansal verileriniz 256-bit SSL şifreleme ve gelişmiş güvenlik duvarları ile korunur. Kişisel bilgileriniz yasal zorunluluklar haricinde üçüncü kişilerle paylaşılmaz.

Tüm işlemleriniz ve bilgileriniz gizlilik politikamız kapsamında korunmaktadır. Kazancasino olarak, kullanıcılarımıza en iyi bonus ve promosyonları sunmayı hedefliyoruz.

Oyun deneyiminizi her zaman eğlenceli ve kazançlı kılmak istiyoruz. Ayrıca, her türlü sorunuz için canlı destek ekibimizden yardım almayı unutmayın. Detaylı bilgi için NetEnt Gizlilik Politikası’na ve [email protected] adresine bakabilirsiniz.

Kazancasino’da kazanç ve eğlence her zaman bir adım ötenizde!

Artılar

- Geniş spor, canlı casino ve slot oyunu seçeneği

- Hızlı ve çok çeşitli ödeme yöntemleri

- 7/24 erişilebilen müşteri desteği

- Cömert bonuslar ve yüksek ödüllü turnuvalar

Eksiler

- Bonus çevrim şartları bazı kullanıcılar için yüksek olabilir

- Tüm ödeme ve bonus seçenekleri her ülkede geçerli değil

- Tek hesap/IP kuralı aile üyeleri için kısıtlama oluşturabilir

9. Ozanbet – Yüksek Kazanç Fırsatı Sunan En Çok Kazandıran Slot Oyunları

Ozanbet, güvenli oyun ortamı ve hızlı işlem prensibi ile dikkat çekiyor. Türkiye’de güvenilir casino siteleri yer alan, müşteri odaklı hizmetiyle binlerce bahis sever için mükemmel bir oyun deneyimi sunuyor.

Canlı casinodan slot oyunlarına ve masa oyunlarına kadar birçok seçenek sunuyor. Ayrıca, 7/24 müşteri desteği ile üyelerine her zaman yardımcı olmayı taahhüt ediyor.

Ozanbet, 2.000’den fazla bahis seçeneği, yüksek oranlar ve güncel karşılaşmalarla Avrupa’nın önde gelen bahis siteleri platformlarından biri olarak öne çıkıyor. Geniş lig seçenekleri, canlı bahis imkanları ve rekabetçi oranlar, her oyuncuya profesyonel bir deneyim sunar.

Ozanbet Casino, 60’tan fazla oyun sağlayıcı ve binlerce slot oyunu ile rakipsiz bir casino deneyimi sunuyor. Özellikle en çok kazandıran slot oyunları, rulet, blackjack, bakara ve poker gibi klasik oyunların yanı sıra, güncellenen canlı casino masaları da sunuyor.

Ozanbet, Curacao Oyun Komisyonu tarafından lisanslı bir platformdur. Uluslararası regülasyonlara uygun şekilde çalışan site, lisanslı casino siteleri arasında güvenliğe verdiği önemle öne çıkar. 256-bit SSL şifreleme, birçok güvenlik duvarı ve gelişmiş veri koruma protokolleri, kullanıcı bilgilerini ve finansal işlemleri yüksek güvenlikle korur.

Ozanbet, hem yeni başlayanlara hem de sadık üyelerine özel olarak hazırladığı bonus kampanyalarıyla rekabette bir adım önde.bonuslara göz attığımızda; Hoşgeldin Bonusu, Kayıp Bonusu,Freespin ve Bedava Bahis,Arkadaşını Getir Bonusu yer alıyor. Hızlı casino deneyimi sunan yapısıyla dikkat çeker.

Bonusların çevrim şartları, kullanım limitleri ve oyun katkı oranları şeffaf biçimde açıklanır. Her promosyon için güncel detaylara ve şartlara “Bonuslar” veya “Promosyonlar” sayfasından ulaşabilirsiniz.

Ozanbet, Para Yatırma ve Çekme Yöntemlerine baktığımız zaman karşımıza Moneytolia,VIP Havale,Jet Banka Transferi Auto Papara / Papara,Payfix, Oto Bank Transfer QR Kod, Jetoncash, Jeton Cüzdan,Kredi Kartı,Cepbank Kripto yöntemleri çıkmaktadır.

Tüm transferler, gelişmiş güvenlik önlemleriyle anında veya kısa sürede yapılır. Ozanbet, 365 gün 24 saat canlı yardım ve e-posta desteği sunar.

E-posta: [email protected]. Reklam, Acentelik, Affiliate için: [email protected]

Artılar

- Geniş oyun yelpazesi ve yüksek oranlı spor bahisleri

- 60’tan fazla sağlayıcı ile binlerce slot ve canlı casino oyunu

- 7/24 canlı müşteri desteği ve hızlı finansal işlemler

- Curacao lisansı ile uluslararası güvenlik ve yasal koruma

Eksiler

- Bonus çevrim şartları yeni kullanıcılar için yüksek görünebilir

- Bazı ödeme ve promosyon seçenekleri tüm ülkelerde kullanılamayabilir

- Tek hesap ve tek IP kuralı aile/ortak kullanımlarda kısıtlama yaratabilir

- KYC (kimlik doğrulama) sürecinde belge talebi zorunlu olabilir

10. Sultanbet – Sağlam Altyapı ve Güçlü Güvenlik ile En Sağlam Bahis Siteleri

Sultanbet, online casino siteleri arasında güvenilirliği, kullanıcı odaklı hizmet anlayışı ve zengin oyun seçenekleriyle öne çıkan bir platformdur. Sultanbet, Türkiye ve dünyada birçok bahis sever için mükemmel bir oyun deneyimi sunar. Modern tasarımı ve mobil uyumluluğu istediğiniz her yerden hızlı ve kolay erişim sağlar.

Sultanbet, 50’den fazla oyun sağlayıcıyla iş birliği yaparak binlerce slot, masa oyunu, canlı casino ve spor bahisleri seçeneği sunar. Sultanbet, güvenilir casino siteleri arasında yer alır. Burada rulet, blackjack, bakara ve poker gibi klasik oyunlar oynayabilirsiniz. Ayrıca, gerçek krupiyelerle oynanan canlı casino masaları da çok popülerdir.

Gelişmiş altyapısı sayesinde hem masaüstü hem de mobil cihazlar üzerinden tüm oyunlara hızlı ve kesintisiz erişim mümkündür.

Kullanıcılar, platformdaki hoşgeldin bonusu, yatırım bonusları, kayıp bonusları ve düzenli turnuvalar sayesinde ekstra kazanç fırsatları elde edebilirler. Ayrıca, freespin, bedava bahis ve arkadaşını getir gibi avantajlar da oyuncuların ilgisini çeker. Tüm promosyonların çevrim şartları ve kullanım kuralları şeffaf bir şekilde açıklanır.

Sultanbet’te kullanılan güncel ve popüler ödeme yöntemler; Para Yatırma ve Çekme Yöntemlerine baktığımız zaman karşımıza Moneytolia,VIP Havale,Jet Banka Transferi Auto Papara / Papara,Payfix, Oto Bank Transfer QR Kod, Jetoncash, Jeton Cüzdan,Kredi Kartı,Cepbank Kripto yöntemleri çıkmaktadır.

Platformun en güçlü yönlerinden biri de, 7 gün 24 saat aktif olan canlı destek hizmetidir. Sultanbet, bahis siteleri ve slot siteleri arasında sunduğu zengin oyun çeşitliliği ve avantajlı kampanyalarla öne çıkar.

Deneyimli müşteri temsilcileri, her konuda hemen yardımcı olur. Hesap yönetimi, bonus talepleri, teknik destek ve ödeme işlemleri gibi konularda destek sağlar.

Yenilikçi bonuslar sunuyor ve kullanıcı dostu bir arayüze sahip. Ayrıca, profesyonel müşteri hizmetleriyle hem yeni başlayanlara hem de deneyimli oyunculara güvenli bir casino deneyimi sağlıyor.

Sultanbet, yüksek güvenlik standartları ve geniş oyun seçenekleri sunar. Ayrıca, cömert promosyonları ve popüler bahis siteleri arasında gösterilmesiyle de dikkat çeker. Bu nedenle, online casino siteleri arasında sağlam bir tercih olarak öne çıkmaktadır.

Artılar

- Güçlü lisans altyapısı ve yüksek güvenlik standartları

- Binlerce slot ve masa oyunu, canlı casino ve spor bahisleri

- Cömert bonuslar, promosyonlar ve turnuvalar

- 7/24 hızlı müşteri desteği ve mobil uyumlu platform

- Geniş ve hızlı ödeme yöntemleri seçeneği

Eksiler

- Bonus çevrim şartları yeni kullanıcılar için karmaşık olabilir

- Bazı ödeme ve promosyon seçenekleri her ülkede geçerli olmayabilir

- Tek hesap/IP kuralı aile/ortak kullanımlarda kısıtlama yaratabilir

- Kimlik doğrulama sürecinde belge talebi zorunlu olabilir

11. Wonodd – Yatırımsız Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler

Wonodd, en yüksek güvenlik standartlarını sunar. Bu platform, Türkiye’de ve dünyada online spor bahisleri ve casino eğlencesinin öncüsüdür.

Lisanslı casino siteleri, arasında yer alan Wonodd, 7/24 kesintisiz müşteri hizmetiyle, kullanıcılarına adil ve keyifli bir oyun ortamı sunar. Platformda futbol, basketbol, tenis gibi popüler sporların yanı sıra, canlı bahis ve binlerce slot/mobil casino oyunu ile eğlence hiç bitmez.

Ayrıca, zengin bahis seçenekleri ve gerçek zamanlı güncellenen canlı bahisler ile spor severlere Avrupa standartlarında bir deneyim yaşatır. Sezgisel ve hızlı bahis altyapısı sayesinde her seviyeden kullanıcı kolayca bahis yapabilir. Bu yönüyle yeni bahis siteleri arasında hızla yükselmektedir.

Yenilikçi masa oyunları ve klasikler, platformda sık sık güncellenir. Bu klasikler arasında slot siteleri, rulet, blackjack, bakara ve poker bulunur.

Tüm bonusların güncel çevrim ve kullanım şartları “Bonuslar” sayfasında şeffaf biçimde paylaşılır. Wonodd, her oyuncu profiline hitap eden deneme bonusu veren siteler arasında öne çıkar.

Yeni üyelere özel yüksek oranlı spor hoşgeldin bonusu sunulurken, slot ve masa oyunlarında geçerli casino hoşgeldin bonusları da ilk yatırımda kullanıcılara avantaj sağlar. Her yatırımda %50 casino yatırım bonusu ile ekstra kazanç fırsatı verilir. Çevrimsiz %15 spor ve casino yatırım bonusu ise, anında ve hızlı çekim avantajı sunar. Ayrıca, her kayıpta yeni başlangıç fırsatı tanıyan anlık %20 casino ve spor kayıp bonusu da mevcuttur.

Wonodd, hızlı ve güvenli para transferleri için Türkiye’nin en popüler ve modern ödeme seçeneklerini sunar.

Kullanıcılar Papara, Jet Papara, banka havalesi ve kredi kartı gibi yaygın yöntemlerle işlem yapabilir. Ayrıca Jet Kripto, My Kripto gibi kripto çözümlerinin yanı sıra anında havale, hızlı havale ve anında QR gibi pratik ödeme imkanları da sunulmaktadır. Cepbank ve diğer elektronik cüzdanlarla bahis siteleri arasında ödeme hızı ve çeşitliklerle dikkat çeker.

Wonodd, alanında uzman müşteri temsilcileriyle 7 gün 24 saat boyunca canlı destek sunar. Canlı destek dışında e-posta ve sosyal medya üzerinden de hızlı iletişim mümkündür. Hesap yönetimi, oyun kuralları veya finansal işlemlerle ilgili her türlü soru ve ihtiyacınızda çözüm odaklı destek sağlanır.

Wonodd, online bahis ve casino dünyasında güvenliğin, eğlencenin ve büyük kazançların buluştuğu adres olmayı sürdürüyor. Güçlü lisans yapısı ve yenilikçi bonusları ile kullanıcı dostu bir arayüz sunuyor. Kazanmanın ve eğlenmenin keyfini yaşamak isteyen herkes için Wonodd her zaman bir tık uzağınızda!

Artılar

- Zengin spor, canlı casino ve slot oyun seçeneği

- Yenilikçi ve güvenli oyun altyapısı (Curacao lisansı, güncel şifreleme)

- Cömert ve çeşitli yatırım/kayıp bonusları, anlık promosyonlar

- 7/24 hızlı ve çözüm odaklı müşteri desteği

Eksiler

- Bonus çevrim şartları yeni kullanıcılar için karmaşık olabilir

- Bazı promosyon ve ödeme yöntemleri her ülkede geçerli olmayabilir

- Tek hesap/IP kuralı, aynı aile veya ortak IP kullanımında kısıtlayıcı olabilir

Casino Siteleri Karşılaştırma Tablosu

Güncel deneme bonusu veren kimsenin bilmediği siteler, bahis dünyasında fark yaratmak isteyen kullanıcılar için eşsiz fırsatlar sunuyor. Aşağıdaki tabloda, bu sitelerin ödeme yöntemleri, mobil uyumlulukları ve yeni üyelere sunduğu özel avantajlar karşılaştırmalı olarak yer alıyor. Bu tabloya gelin birlikte bakalım.

| Site Adı | Lisans & Güvenlik | Bonuslar | Oyun Çeşitliliği |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akcebet | Curacao lisansı, güçlü altyapı, şifrelem | Limitsiz & çevrimsiz bonuslar, kayıp, arkadaş getir | 2000+ bahis, slot, canlı casino |

| Alibahis | Curacao lisansı, | Hoşgeldin, yatırım, kayıp, freespin, deneme bonusları | 60+ sağlayıcı, binlerce oyun, canlı casino |

| Betbaba | Curacao lisansı, güçlü altyapı, şifreleme | Limitsiz & çevrimsiz bonus, kayıp, arkadaş getir | 2000+ bahis, slot, canlı casino |

| Betivo | Curacao lisansı, gelişmiş güvenlik | Kayıp, yatırım bonusları, özel promosyonlar | Spor, canlı casino, slot, turnuvalar |

| BTCbahis | Curacao lisansı, kripto öncelikli güvenlik | Kripto yatırım bonusları, kayıp, çevrimsiz bonuslar | Spor, casino, slot, kripto oyunlar |

| Casinomega | Curacao lisansı, veri koruma, hızlı çekim | Yatırım, kayıp, hoşgeldin, free spin | Slot, canlı casino, masa oyunları |

| EfesCasino | Lisanslı altyapı, gelişmiş güvenlik | Hoşgeldin, yatırım, kayıp, VIP bonusları | Casino, canlı casino, slot, masa oyunları |

| Kazancasino | Lisanslı altyapı, güçlü güvenlik protokolleri | Yatırım, kayıp, anlık bonuslar, büyük turnuvalar | Spor, canlı casino, slot, masa oyunları |

| Ozanbet | Curacao lisansı, 256-bit SSL, kimlik doğrulama | Hoşgeldin, yatırım, kayıp, freespin, deneme bonusu | 60+ sağlayıcı, binlerce oyun, canlı casino |

| Sultanbet | Curacao eGaming lisansı, 256-bit SSL, veri koruma | Hoşgeldin, yatırım, kayıp, turnuva, freespin, arkadaş getir | 50+ sağlayıcı, binlerce slot/masa, canlı casino, spor bahisleri |

Türkiyede yasal bahis siteleri nelerdir?

Türkiye’de yasal bahis siteleri, devlet tarafından lisanslandırılmış ve sıkı bir şekilde denetlenen platformlardır. Ülkemizde yasal olarak spor bahisleri oynatabilen iki ana kurum bulunmaktadır: Spor Toto Teşkilat Başkanlığı ve İddaa. Bu kurumlar, resmi internet siteleri ve bayileri aracılığıyla yasal bahis hizmeti sunar. Ayrıca, Türkiye Jokey Kulübü (TJK) de at yarışları için yasal bahis imkânı sağlar.

Yasal bahis siteleri, kullanıcıların güvenli bir ortamda bahis yapmalarını sağlamak amacıyla, finansal işlemler ve kişisel veri güvenliği açısından sıkı önlemler uygular. Tüm işlemler, uluslararası standartlara uygun şekilde şifrelenir ve denetlenir. Bu sitelerde üyelik oluşturmak ve bahis yapmak tamamen yasal olup, herhangi bir yasal sorunla karşılaşılmaz. Ayrıca, ödeme işlemlerinde hızlı ve sorunsuz hizmet sunulmaktadır.

Yasal bahis siteleri, kullanıcılarına çeşitli spor dallarında bahis yapma olanağı sunarken, düzenli olarak promosyon ve bonuslar da sağlar. Ayrıca, canlı bahis seçenekleri, yüksek oranlar ve kolay erişim gibi avantajlar ile sektördeki popülerliğini korur. Kaçak ya da lisanssız bahis sitelerinde oynamak ise hem maddi kayıplara yol açabilir, hem de yasal yaptırımlarla karşılaşılmasına neden olabilir. Bu nedenle, bahis yapmak isteyen kullanıcıların sadece devlet tarafından onaylanmış ve lisanslı platformları tercih etmesi büyük önem taşır.

Deneme Bonusu Veren Siteler Hangileridir?

Türkiye’de ve dünyada öne çıkan birçok bahis ve casino sitesi, yeni üyelere deneme bonusu sunarak kullanıcılarına risksiz bir şekilde platformu tanıma imkanı sağlar. 2026 yılı itibarıyla deneme bonusu veren güvenilir siteler arasında Akcebet, BTCbahis, Casinomega, Ozanbet, Kazancasino, EfesCasino, Alibahis ve Wonodd gibi popüler platformlar öne çıkıyor. Bu siteler, genellikle kayıt olduktan sonra veya belirli bir doğrulama işlemi sonrasında kullanıcılarına ücretsiz deneme bakiyesi tanımlar.

Deneme bonusu, özellikle yeni başlayanlar için oldukça avantajlıdır. Kullanıcılar bu bonus ile, siteye yatırım yapmadan slot oyunları, canlı casino veya spor bahislerinde şansını deneyebilir ve sistemi yakından tanıyabilir. Ayrıca, bu bonuslar çoğunlukla çekilebilir bakiyeye dönüşme şansı da sunar, fakat çevrim şartlarını yerine getirmek gerekir.

Slot oyunları neye göre ödeme yapar?

Slot oyunlarında ödeme, genellikle oyunun kendi ödeme tablosuna (paytable) ve oyun sırasında elde edilen sembol kombinasyonlarına göre belirlenir.

Her slot makinesinin kendine özgü bir ödeme tablosu vardır ve burada hangi sembollerin, hangi sıklıkta ve ne kadar kazanç sağladığı ayrıntılı şekilde gösterilir. Örneğin, nadir çıkan özel semboller veya wild/scatter gibi simgeler, genellikle daha yüksek ödemeler sunar.

Slot oyunlarının ödeme oranını belirleyen en önemli faktörlerden biri de “RTP” yani “Return to Player” değeridir. RTP, oyuncuya uzun vadede ödenmesi beklenen yüzdelik oranı ifade eder. Örneğin, bir slot oyununun RTP’si %96 ise, bu oyun teorik olarak yatırılan her 100 TL’nin 96 TL’sini oyunculara çeşitli zamanlarda geri öder. Ancak kısa vadede büyük kazançlar da olabilir, kayıplar da yaşanabilir; bu tamamen oyunun rastgeleliğine ve şansa bağlıdır.

Ayrıca, slot oyunlarında ödeme yapısı “sabit” veya “değişken” (volatile) olabilir. Düşük volatiliteye sahip oyunlar sık sık ama küçük kazançlar verirken, yüksek volatiliteye sahip oyunlar daha seyrek fakat büyük ödemeler yapabilir.

Sonuç olarak, slot oyunlarının ödeme mekanizması tamamen rastgele çalışan bir yazılım olan RNG (Random Number Generator) tarafından belirlenir. Bu nedenle her çevirme birbirinden bağımsızdır ve oyunlar lisanslıysa manipülasyon ihtimali yoktur. Oyuncular, ödeme tablosunu ve oyunun özelliklerini inceleyerek kendi oyun stratejilerini geliştirebilirler.

Sonuç

Online şans oyunları dünyasında, casino siteleri kullanıcıların eğlenceli ve kazançlı vakit geçirebileceği dijital platformların başında geliyor. Son yıllarda teknolojinin gelişmesiyle beraber, artık dilediğiniz her yerden, masaüstü ya da mobil cihazlarla casino sitelerine kolayca erişmek mümkün. Ama, piyasada yüzlerce farklı casino sitesi var. Bu, oyuncuların hangi platformun güvenilir ve avantajlı olduğunu anlamasını zorlaştırıyor.

Casino siteleri seçerken en kritik kriterlerin başında lisans ve güvenlik gelir. Lisanslı ve yasal siteler, kişisel verilerinizi korur ve adil oyun ortamı sağlar. Özellikle Curacao veya Malta gibi uluslararası otoritelerden lisans almış platformlar, bu alanda öne çıkar. Bunun yanı sıra, kullanıcı yorumları ve sektör incelemeleri, güvenilir casino seçimi yaparken önemli bir referans noktasıdır.

Bunun yanında, casino siteleri arasında karar verirken bonus kampanyalarına ve ödeme yöntemlerine de dikkat etmek gerekir. Hoş geldin bonusları, yatırım bonusları ve kayıp bonusları gibi çeşitli promosyonlar sunan casino siteleri, oyunculara ekstra avantaj sağlar. Ancak, bu bonusların çevrim şartları ve kullanım kuralları mutlaka incelenmelidir. Ayrıca, hızlı ödeme seçenekleri ve çeşitli para yatırma-çekme yöntemleri sunan casino siteleri uzun vadede kullanıcı memnuniyetini artırır.

En iyi online casinolar, sahip oldukları geçerli lisanslar ve yüksek güvenlik standartlarıyla oyunculara güvenli bir oyun ortamı sunar. Bu platformlar, avantajlı bonus kampanyaları ve çok sayıda ödeme seçeneği ile kullanıcıya ekstra fırsatlar sağlar. Ayrıca kullanıcı dostu arayüzleri ve sorunsuz deneyimi sayesinde hem yeni başlayanlar hem de deneyimli oyuncular için eğlenceli ve konforlu bir oyun deneyimi sunar.

Siz de bu temel unsurları dikkate alarak, güvenilir ve avantajlı casino siteleri ile online şans oyunlarının tadını güvenle çıkarabilirsiniz. Seçiminizi bilinçli yaparak, hem eğlenceli hem kazançlı bir oyun deneyimi yaşayabilirsiniz.

Sık Sorulan Sorular

1. Casino siteleri yasal mı?

Türkiye’de faaliyet gösteren casino sitelerinin büyük bir bölümü yurtdışı merkezlidir ve Türkiye’de resmi olarak lisanslı değildir.

Ancak, Curacao, Malta gibi uluslararası lisanslara sahip siteler, güvenlik ve adil oyun açısından tercih edilebilir.

2. En güvenilir casino sitesi hangisi?

En güvenilir casino siteleri, uluslararası geçerli lisanslara, güçlü veri güvenliği altyapısına ve şeffaf ödeme politikalarına sahip olanlardır.

Kullanıcı yorumları, hızlı ödeme ve müşteri memnuniyeti de seçimde önemlidir.

3. Casino sitelerine nasıl üye olunur?

Bir casino sitesine üye olmak için genellikle ana sayfada bulunan “Kayıt Ol” ya da “Üye Ol” butonuna tıklayarak,

kişisel bilgilerini ve iletişim bilgilerini doldurmak yeterlidir. Ardından üyelik onay e-postası ile hesabını aktifleştirebilirsin.

4. Casino siteleri deneme bonusu veriyor mu?

Birçok casino sitesi, yeni üyelere veya promosyon dönemlerinde yatırımsız deneme bonusu sunar.

Bu bonuslar genellikle siteyi denemen için küçük bir bakiyeyi veya ücretsiz dönüş hakkını içerir.

5. Yatırımsız deneme bonusu nedir?

Yatırımsız deneme bonusu, herhangi bir para yatırmadan alınabilen ücretsiz bakiyedir.

Kullanıcıların siteyi risksiz denemesi için sunulur ve genellikle çekim şartları veya belirli oyunlarda kullanılma zorunluluğu bulunur.